Difference between revisions of "The Wire - The Lost Tapes"

Martinwguy (talk | contribs) m (Martinwguy moved page The Lost Tapes to The Wire - The Lost Tapes) |

Martinwguy (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

An article '''Delia Derbyshire - The Lost Tapes''' appeared in '''The Wire''' magazine November 2008 (Issue 297), p.12 mostly based on an interview with [[David Butler]]. | An article '''Delia Derbyshire - The Lost Tapes''' appeared in '''The Wire''' magazine November 2008 (Issue 297), p.12 mostly based on an interview with [[David Butler]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <BR CLEAR=ALL> | ||

| + | =Transcript= | ||

| + | <CENTER><B>Delia Derbyshire</B><BR> | ||

| + | The lost tapes</CENTER> | ||

| + | <P> | ||

| + | "My understanding of Delia as a composer has been completely changed since hearing about these tapes." David Butler is talking about the private tape archive of BBC Radiophonic Workshop doyenne Delia Derbyshire, which Manchester University have just acquired and digitised. 2008 marks the Workshop's 50th anniversary, and it's already seen the work of Derbyshire's colleague John Baker strip-mined for a brace of Trunk releases. This month Mute are set to reissue the Workshop's much-admired album collections from 1968 (''BBC Radiophonic Music'') and 1975 (''The Radiophonic Workshop'') on CD, alongside a two CD anthology spanning the department's entire history. | ||

| + | <P> | ||

| + | The Derbyshire archive, then, comes as the icing on the cake. Stored by the musician herself in huge, tattered Kellogg's cereal boxes, upon her death in 2001 the collection was bequeathed to Workshop archivist Mark Ayres. Recognising the historical importance of the haul, Ayres began negotiations for a lasting solution with Butler, a lecturer in Screen Studies, and the Derbyshire estate. Just as the recordings of Workshop pioneer Daphne Oram have recently become a permanent resource at Goldsmiths College in London, so too had Derbyshire's music found a lasting home on Manchester's Oxford Road. | ||

| + | <P> | ||

| + | Contained in those cardboard boxes were 267 tape reels, each around 30 minutes long, covering both Derbyshire's BBC work and her subsequent freelance ventures. They range from full ambient scores for theatre productions to embryonic sketches of some of her bet know work. The project has required some dedicated detective work. On their arrival with Butler at the university, some of the reels, and their identifying labels, were rattling loose from their spindles. Simply playing the outmoded tapes posed a major hurdle, but, as Butler reveals, serendipity stepped in. "The BBC's Oxford Road studios in Manchester were getting rid of an old Studer A80 deck," he says, "They just didn't need it any more, and they very generously loaned it to us. It plays beautifully, that machine." | ||

| + | <P> | ||

| + | After a year spent transferring the tapes, the archive's existence has now been formally announced. Already the music that's been unearthed has been attracting attention. One brief, rhythmic snippet has been likened to cutting edge dance music, sparking online rumours that the piece was an academic hoax, but it's definitely genuine, Derbyshire's tapes contain several examples of what Butler describes as "really aggresive, nasty rhythm tracks" that confound her reputation as a creator of gentle, ambient music. | ||

| + | <P> | ||

| + | As yet, the whole project is still in its early stages. Once funding is in place, Manchester University has plans to create a full-time archivist post, and launch symposia and concerts responding to Derbyshire's music. Music fans at large will have access to the recordings, too, "That's an absolute must," reckons Butler. "If we didn't make this available to people outside academia we wouldn't be honouring Delia's approach to her music. She bridged the experimental and the popular, and that's one reason why for some years she wouldn't have been acknowledged in - I hate the label - 'serious' music circles, because of that association with functional music. But that's precisely why she's had the influence that she's had." It's intended that, one day, interested partied will be able to hear the recordings in the listening suites at the university. "That probably won't happen for several years," Butler admits, "but that's the long-term aim." <B>Andy Murray</B> | ||

[[Category:Article]] | [[Category:Article]] | ||

Latest revision as of 00:47, 30 January 2021

An article Delia Derbyshire - The Lost Tapes appeared in The Wire magazine November 2008 (Issue 297), p.12 mostly based on an interview with David Butler.

Transcript

The lost tapes

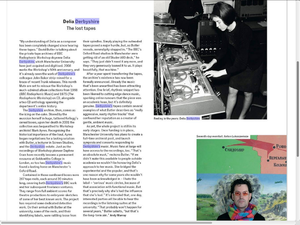

"My understanding of Delia as a composer has been completely changed since hearing about these tapes." David Butler is talking about the private tape archive of BBC Radiophonic Workshop doyenne Delia Derbyshire, which Manchester University have just acquired and digitised. 2008 marks the Workshop's 50th anniversary, and it's already seen the work of Derbyshire's colleague John Baker strip-mined for a brace of Trunk releases. This month Mute are set to reissue the Workshop's much-admired album collections from 1968 (BBC Radiophonic Music) and 1975 (The Radiophonic Workshop) on CD, alongside a two CD anthology spanning the department's entire history.

The Derbyshire archive, then, comes as the icing on the cake. Stored by the musician herself in huge, tattered Kellogg's cereal boxes, upon her death in 2001 the collection was bequeathed to Workshop archivist Mark Ayres. Recognising the historical importance of the haul, Ayres began negotiations for a lasting solution with Butler, a lecturer in Screen Studies, and the Derbyshire estate. Just as the recordings of Workshop pioneer Daphne Oram have recently become a permanent resource at Goldsmiths College in London, so too had Derbyshire's music found a lasting home on Manchester's Oxford Road.

Contained in those cardboard boxes were 267 tape reels, each around 30 minutes long, covering both Derbyshire's BBC work and her subsequent freelance ventures. They range from full ambient scores for theatre productions to embryonic sketches of some of her bet know work. The project has required some dedicated detective work. On their arrival with Butler at the university, some of the reels, and their identifying labels, were rattling loose from their spindles. Simply playing the outmoded tapes posed a major hurdle, but, as Butler reveals, serendipity stepped in. "The BBC's Oxford Road studios in Manchester were getting rid of an old Studer A80 deck," he says, "They just didn't need it any more, and they very generously loaned it to us. It plays beautifully, that machine."

After a year spent transferring the tapes, the archive's existence has now been formally announced. Already the music that's been unearthed has been attracting attention. One brief, rhythmic snippet has been likened to cutting edge dance music, sparking online rumours that the piece was an academic hoax, but it's definitely genuine, Derbyshire's tapes contain several examples of what Butler describes as "really aggresive, nasty rhythm tracks" that confound her reputation as a creator of gentle, ambient music.

As yet, the whole project is still in its early stages. Once funding is in place, Manchester University has plans to create a full-time archivist post, and launch symposia and concerts responding to Derbyshire's music. Music fans at large will have access to the recordings, too, "That's an absolute must," reckons Butler. "If we didn't make this available to people outside academia we wouldn't be honouring Delia's approach to her music. She bridged the experimental and the popular, and that's one reason why for some years she wouldn't have been acknowledged in - I hate the label - 'serious' music circles, because of that association with functional music. But that's precisely why she's had the influence that she's had." It's intended that, one day, interested partied will be able to hear the recordings in the listening suites at the university. "That probably won't happen for several years," Butler admits, "but that's the long-term aim." Andy Murray