The BBC Radiophonic Workshop: The First 25 Years

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop: The First 25 Years: the inside story of providing sound and music for television and radio, 1958-1983 is a book by Desmond Briscoe and Roy Curtis-Bramwell published in 1983 by the BBC in London.

It contains 12 pages about Delia.

Extracts

Page 26

In 1963 a Workshop composer called Delia Derbyshire realised by a series of ‘carefully times hand-swoops’ on twelve small oscillators the signature tune for a new children's series called Doctor Who. The story of how this momentous event came about is described in chapter 8.

Pages 82-86

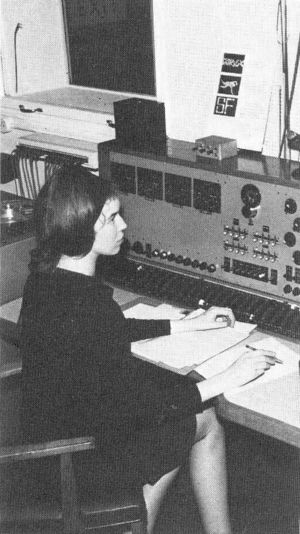

Delia Derbyshire (1962-1973)

It's a suitable name for legends: and certainly a number of anecdotes about Delia crop up in the reminiscences of the time when she — together with Desmond Briscoe, Brian Hodgson, John Baker and David Cain — formed what some people look back upon as one of the golden ages of the Radiophonic Workshop.

One tale concerns her creation of the biggest loop of recording tape ever seen in the history of the world. It circled her studio several times, looped gracefully out of the door and down the corridor as far as the commissionaire's desk at the entrance of BBC Maida Vale Studios, and back again. Not everyone believes that one.

Another story concerns her minor classic of radiophonic music, the signature tune to Great Zoos of the World. It was apparently created overnight, with a little help from her friends, and completed just in time for the surprised and delighted programme producer who had come up specially from Bristol to take away a piece created entirely from the sounds of real animals.

Born in Coventry, and trained as a pianist, Delia read mathematics and music at Cambridge University and joined the Workshop team in 1962. Delia came to us very highly qualified indeed, says Descomnd Briscoe. At first she asked whether she could spend her days off sitting quietly in a corner and watching us work. We replied: ‘Yes of course.’ So this tall, quiet, auburn-haired young lady came over from Broadcasting House whenever she wasn't working as a studio manager, and watched us. Later she stayed on to contribute an enormous amount of very beautiful — almost unearthly — and quite remarkable music. Some of her pieces like The Delian Mode and Blue Veils and Golden Sands are without parallel in our output.

Few people can write witty music, but Delia could. She was an original worker who used an analytical approach to synthesise complex sounds from electronic scores. The mathematics of sound came naturally to her and she could take a set of figures and build them into music in a way quite different from anyone else.

Delia was also one of the first people to overcome the criticism that radiophonic music was always horrific. She really gave the lie to that often repeated saying that it was easy to be horrid, reasonable easy to be amusing, pretty difficult to be pompous and grandiose, and very difficult indeed to be beautiful.

It was Delia who first realised electronically Ron Grainer's music for the Doctor Who signature tune. Delia's ability to take on enormous projects to order was to be shown again much later when she composed a special extended electronic piece for the Institute of Electrical Engineers which was performed before the Queen and Prince Philip at the Royal Festival Hall. Taking the initial letters IEE, Delia composed music from their mathematical correspondences and from Morse code: introducing elements of the development of electricity in communication from the earliest telephone to the Americans landing on the moon. There was the voice of Mr Gladstone congratulating Mr Edison on inventing the phonograph: the opening and closing down of Savoy Hill with Lord Reith's voice: and Neil Armstrong speaking as he stepped onto the surface of the moon. The powerful punch of Delia's rocket take-off threatened the very fabric of the Festival Hall.

Her collaboration with writer Barry Bermange in the Third Programme series of four programmes called Inventions for Radio, was most distinguished. For Dreams, Bermange had first recorded a number of people talking about their dreams and then analysed the resulting conversations into subjects. Together, he and Delia built up a word pattern which was then set to pure electronic sound. For the second programme in the series Amor Dei it was decided to use no electronic sounds at all. At one point, Barry Bermange said that he would like ‘the sound of a Gothic altarpiece’. ‘Show me,’ said Delia. So Bermange drew a beautiful Gothic altarpiece and said: ‘That sort of sound.’ Using human voices and developing the use of sung words on tape, Delia provided what he wanted.

That was music to take seriously, of course, says Delia. But I always immensely enjoyed doing funny programmes. There was one called Family Car, a do-it-yourself maintenance programme, for which they wanted lighthearted cartoon-type music. I worked out the four-stroke cycle of an engine and made suitable push … suck … bang … blow … noises. I used the tune Get Out and Get Under, but I made it on simulated car horns and cut it together very carefully. The music worked all right, but it was turned down because one particular car had been used for the series and the manufacturer's didn't really want my efforts to be associated with their product.

A classic case of ‘coals to Newcastle’ occurred during this time following a visit to the Workshop by a freelance German broadcaster. His interviews with the Maida Vale radiophonic music composers were built into a radio programme which proved so successful that Munich Radio approached the BBC with a polite request for a radiophonic signature tune for their daily news programme, which had since the war been heralded by an Eric Coates March. The BBC agreed, and the Workshop accepted the commission eagerly, thinking it an honour to be asked to export electronic sounds to the country that had first pioneered them. Delia Derbyshire composed the theme, and on the first evening that it was heard on air the German announcer duly credited and thanked the ‘Britisher’ lady composer who was responsible for the piece.

p.86:

[...] all night towards what I wanted, but when the dawn came I felt I had so much more that I needed to do. Then the cleaning lady came in and I asked her what the music reminded her of. ‘The North Pole,’ she replied. Right, I thought, I'm not going to muck about with it any longer.

Where other Workshop composers think in terms of visual images or colours, Delia considered everything in a very analytical way.

Availability

- It is hard to find an original; when a copy does appear on abebooks.it or eBay, it costs from fifty to a hundred pounds.

- There is a searchable version on Google Books